The Philippines is formally a democracy; citizens vote, and many government institutions have public accountability measures. But, as most political scientists will tell you, a healthy democracy needs more than democratic institutions. Beyond elections, public accountability mechanisms for public officials, and other formal measures, vibrant democracies require strong democratic cultures.

The ontological hurdle of definition notwithstanding, engineering this culture is a difficult long-term task, accomplished through changing mindsets rather than writing new rules. Democracy, if it is to be defined as a system of governance that allows citizens to exercise reasonable control over their own interests, requires an assertive citizenry capable of challenging authority when it encroaches on individual or group autonomy.

This disposition may strike some Filipinos as too combative, especially since many of us prefer to avoid conflict and espouse so-called “Asian values” like deference to authority and smooth interpersonal relationships. To engage in polemics, to play the gadfly, to speak truth to power, or simply to be different, disrupts a romanticized oneness.

In a society saturated of faux nationalisms manifested in polo shirts with images of a unified Philippine archipelago, “magkaisa” becomes an end in itself, neglecting how the unity myth breaks down once injustices reveal the necessity of consensus-breaking dissent. Fortunately or unfortunately, democracy is dangerous, and being a democratic agent requires guts. Passivity is antithetical to active citizenship (and this is more than a semantic point).

So how do we combat the cultural inertia that the powerful exploit to maintain numbing and boring homogeneity? Well, you target the young.

The first day my students enter my classroom in Ateneo de Manila, I tell them to help me run a “democratic classroom.” By this I simply mean a learning environment that encourages free thought and speech. So while, as a teacher, I still grade my students and exercise a reasonable degree of authority, I try not to draw attention to this power. For one thing, I’d rather my students call me “Leloy” than “sir.” More importantly, I encourage them to argue with their classmates and me. Some of them are initially hesitant to do so, fearing that disagreeing with the teacher leads to low grades. One of my main goals as a teacher is to dispel this notion, and, when I accomplish this, classroom discussions become fruitful. When I don’t, they become tedious.

I am by no means the an expert in pedagogical approaches, but my own experience makes me believe that students can learn more from a liberal education rather than one based on unnecessary hierarchies. Empowered students are active students, and active students are democratic agents. Unfortunately, our educational system is structured in a way that ensures student passivity. For instance, how can we expect students to participate in campus politics when administrations systematically disempower them?

Why do students rarely get seats in the highest decision making bodies of universities and colleges?

Democracy entails the representation of major stakeholders in decision-making bodies. It just doesn’t make sense for colleges and universities to privilege the voices of powerful businessmen over their own students.

And when students assert their rights, they become subject to repression. Some cases, such as that of Regina Mae Alog, student regent of the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Pasay, are blatant. Alog was dismissed without due process when she examined anomalies in the university budget.

Other acts of repression are more subtle and insidious. In Ateneo, purportedly one of the country’s more liberal educational institutions, the Office of Student Organizations (OSA) micromanages student organizations through a rigorous accreditation system that allows them to monitor everything including when student organizations can meet. How can students develop the skills necessary for responsible self-governance when the administration is constantly breathing down their necks?

When left to their own devices, university and college administrations insist on their untrammelled authority, and, in the case of private institutions, they use “private rights” and autonomy to justify the most abhorrent policies. This is what Don Bosco did when they once required students to take “masculinity tests” as an admission requirement.

We live in a culture that treats college and university students as children instead of citizens with rights. And while student groups in selected institutions may win occasional battles here and there, we need a broad framework that guarantees student rights nationally. Since what is at stake here is the formation of democratic agents, this is an area where the state should limit the powers of even private institutions.

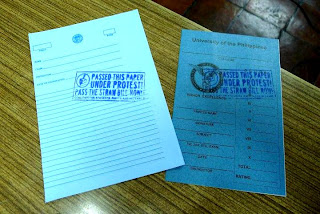

The Students Rights and Welfare (STRAW) Bill proposed by Akbayan Representatives Walden Bello and Kaka Bag-ao does precisely this. The bill, apart from setting minimum rights and guarantees of students (e.g. the right to a free and financially independent student government) has targeted provisions that will prevent some of the abuses detailed above. The bill ensures student representation in the highest decision–making bodies of colleges and universities, it allows them to draft their own accreditation guidelines, and it ensures that school administrations grant students access to information to official records and documents.

It is about time for us to for us to recognize that institutions of higher learning should not be exempt from the democratic values that we should collectively espouse. If, at a young age, citizens do not understand that values of representation, autonomy, and rights, the Philippines will have all the formal democratic structures without the culture necessary to animate it.

x x x

Lisandro Claudio (“Leloy”) is a PhD Candidate at the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, the University of Melbourne. He is the national chairperson of Akbayan Youth.